By Laura L. Acosta

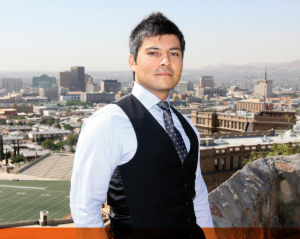

While working on an air pollution study his senior year at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez (UACJ), Hector Olvera, Ph.D., realized how something as benign as taking a breath could be hazardous to a person’s health.

Environmental Resource Management, is working to create a clearinghouse of air

quality information at UTEP that can be used by health researchers for future studies.

A native of Juárez, Mexico, Olvera planned to become a structural engineer. He was awarded a scholarship to attend graduate school in Canada once he received his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from UACJ in 1999. But his plans changed after he designed a low-emission brick kiln, which reduced particle pollution by 90 percent.

“I got hooked,” recalled Olvera, a research assistant professor at UTEP’s Center for Environmental Resource Management. “I had taken a bioethics class in high school, so I was already very passionate about the environment. But it was there (in the lab) that I thought, ‘I want to do this for a living.’”

He forfeited his scholarship and enrolled at The University of Texas at El Paso, where he earned a master’s in environmental science in 2002 and a Ph.D. in environmental science and engineering four years later.

Instead of designing bridges or tunnels, Olvera is integrating engineering principles to develop solutions to environmental health problems.

Since August 2012, the environmental health engineer has been applying the same concept to his air quality research at the Hispanic Health Disparities Research Center (HHDRC) at UTEP.

Established in 2003 with support from the National Institutes of Health, the HHDRC is a collaborative effort between the School of Nursing and College of Health Sciences at UTEP and The University of Texas at Houston School of Public Health, El Paso Regional Campus. The center’s aim is to research and eliminate racial and ethnic health inequalities across the nation.

“Dr. Olvera brings in the environmental side and nurses bring in the health care side, and together we build a synergy to look at environmental health indicators that impact health, like pollution and its effects on the lungs,” said Elias Provencio-Vasquez, Ph.D., nursing school dean and the HHDRC’s administrator.

As a member of the center’s environmental core, Olvera helps researchers investigate the determinants of environmental health disparities in Hispanic populations. He is mapping areas of El Paso to indicate zones with the highest and lowest pollution levels, which will help researches identify populations that are at risk for respiratory conditions or heart disease.

According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the health effects of air pollution include respiratory diseases such as asthma, cardiovascular diseases, changes in lung function, and death.

Ultrafine particles from diesel vehicle emissions can travel from the lungs into the bloodstream and reach the heart, brain, kidneys and bone marrow, Olvera said.

“When you study environmental health, you look at whether the environment can cause a disease,’” he explained. “At the core of health disparities is the socioeconomic component. If everybody made a similar income, then everyone could afford to live in a healthier environment and have access to health care.”

By working closely with nursing school faculty, Olvera’s input will make it possible for nurses to become more aware of the environmental health risks to which their patients are susceptible.

This year, Olvera launched a study to see if traffic emissions put elderly Hispanics at higher risk for a second heart attack.

“After a heart attack, a caregiver may tell patients what foods to avoid and how to keep down their cholesterol levels,” Olvera said. “They’re educating patients on all the known health risk but there are also environmental risks that patients should be told to avoid. I think our nurses would be better prepared if they also understand this part of the problem.”

Olvera’s goal is to build on data that he collects while working with researchers to create a clearinghouse of air quality information at UTEP that will be valuable for future studies.

The work is already paying dividends. A map that Olvera created a few years ago is being used by Rodrigo X. Armijos, M.D., Sc.D., associate professor of public health sciences, to investigate the adverse effects of air pollution on the cardiovascular health of children. Olvera is working with Armijos to set up portable air monitoring stations around schools in El Paso to see if transient exposure to high levels of air pollution causes oxidative stress and systemic inflammation in elementary school-aged children.

Olvera’s air monitoring data has also contributed to two transdisciplinary studies at the HHDRC that involve Sara Grineski, Ph.D., co-director of the environmental core and assistant professor of anthropology, and Timothy Collins, Ph.D., associate professor of geography.

The first study looked at disparities in children’s lung health. Collins and Grineski worked on a social survey related to respiratory health, while Olvera conducted air quality monitoring to develop a surface map of air pollution for the El Paso Independent School District. Researchers combined the data to determine the impact of particulate matter on children’s respiratory health.

The researchers will next study the effects of daily air pollution on respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations among Hispanics in El Paso.

With help from research assistants Gabriel de Haro and Omar Jimenez, and El Paso Water Utilities, Olvera sets up air monitoring stations next to water wells throughout the city. After collecting particle matter samples and analyzing the data, he creates land use regression models to assess air quality conditions in neighborhoods.

The experience has allowed de Haro to develop the critical thinking and analytical skills he needs to pursue a career as an environmental health engineer.

“[Olvera] trains his students to be more effective, so when they go out to the real world to work, they will be prepared and be successful,” said de Haro, an undergraduate civil engineering major.

Olvera expects his air quality maps will help researchers design better studies, produce more competitive proposals, and create a more innovative research program.

“We really need to know our region to be able to study what happens within,” he said. “I think the work that I’m doing is a strong foundation, and we are really getting to know where our problems are.”