By Nadia M. Whitehead

UTEP News Service

Fruit flies under the influence of alcohol exhibit similar characteristics to intoxicated humans.

As their blood alcohol content rises, they become more and more hyperactive, and even promiscuous. And just like humans, once they’ve had too much, they start to slow down and eventually pass out.

“Alcohol in fruit flies induces all kinds of behavior that is very similar to humans,” said Kyung-An Han, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences at The University of Texas at El Paso who has been studying the effects of alcohol on fruit flies for the past seven years. “Their behavior fits really nicely with how people define disinhibition – when people drink they do all kinds of things they wouldn’t normally do, like become more aggressive, promiscuous and talkative.”

In the case of humans, there are two types of disinhibitions that occur when one drinks: motor and cognitive. Aggressive acts or fighting and short tempers would be motor disinhibitions, while becoming more promiscuous, binge drinking or driving under the influence are cognitive effects.

Similar disinhibitions are seen when flies get drunk. They tend to fly on impulse and bump into each other or to the wall, which they normally wouldn’t do, and they become more promiscuous, even with other males, which is not typically seen without alcohol.

“Although the fly and human brain structures are not the same, what’s happening in those places could be quite similar because the output is similar,” said Han, who is the director of the Neuroscience and Metabolic Disorders Project at UTEP.

She recently received more than $448,500 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to study the mechanisms in the fly brain that underlie these disinhibited behaviors, and how dopamine, a key brain molecule for pleasure and addiction, is linked to these alcohol-induced disinhibitions.

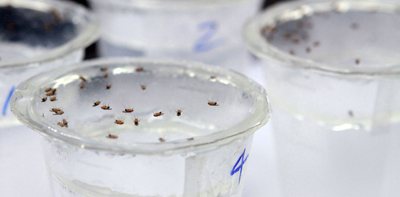

Paul Sabandal, a graduate student studying biology at UTEP and a member of Han’s research team, described the fruit fly experiments. The insects are placed in ‘The Fly Pub’ – a small chamber that slowly releases ethanol vapor and gets the flies drunk.

“We do this for six consecutive days,” he said. “In the first exposure, they’re not used to alcohol so they sedate rather quickly. Over the next few days, they develop tolerance and take longer to sedate, much like humans do.”

For the study, the team investigates both types of impulsivities that occur when under the influence, but with focus on cognitive disinhibitions – like not thinking about the consequences of binge drinking or drunk driving– because that’s what leads to detrimental consequences such as alcohol addiction, violence and fatal traffic accidents.

Dopamine plays a role because it increases when one takes alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamines, and other addicting substances. In other words, pleasure increases with dopamine neurotransmission, which is why they are potentially addictive substances.

“Dopamine is important for the reward circuit of the brain in humans and other animals,” Sabandal said. “Increased dopamine leads to euphoric effects and this is what drug abusers and alcoholics look for – a sort of high. If we can observe changes in the dopamine system of flies by exposure to alcohol, this might suggest that similar changes happen in humans too.”

The team’s experiments have shown that when ethanol is taken and dopamine increases, flies become more promiscuous because courtship is a pleasurable act. In the same way, when humans drink, dopamine increases. People become more promiscuous and they also seek to increase the feeling of pleasure by excessive or binge drinking.

Han’s goal is to pinpoint exactly where in the fly brain dopamine mediates cognitive disinhibitions that occur with alcohol use. Identifying the mechanism could lead to a way to decrease the behaviors that lead to addiction and abuse.

Robert Kirken, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Biological Sciences, explained, “If you can understand regions of the brain or those molecules that are responding and promoting the addiction, then it may be possible to identify drugs that perhaps can block the pathways so that you can minimize or reduce that uncontrolled desire to abuse those substances.”

The team has already seen interesting results from manipulating different regions of the fly brain.

For instance, when dopamine signaling is completely shut off and the fruit flies are exposed to alcohol, they demonstrate negligible courtship, or disinhibited behavior. Why? Because they no longer have the “template” for pleasure.

Jose Luis Gutierrez, an undergraduate majoring in kinesiology, is working on an experiment that slightly increases and decreases dopamine levels in the brain of the fruit fly. He hopes it will pinpoint the area of the brain that mediates the dopamine signal for disinhibition.

“So far, Jose’s work suggests that the mushroom body neurons maybe be critical for ethanol induced cognitive disinhibtion,” Han said. “And the mushroom body brain structure in the fruit fly tends to be very similar to the hippocampus in humans.”

Han expects to have the full results sometime soon.

“To study the human brain would be great, but it’s extraordinarily complex,” Kirken said. “If you want to understand certain regions or molecules that are in the brain and how they function, well we can’t really manipulate humans, but we can manipulate flies so that we can understand the proteins and pathways that we share with them.”

Han would eventually like to work with human subjects by building a connection with a community outreach center in the El Paso area.

She said, “We know that we can’t stop people from drinking, so why not learn about how it affects our brain so that we can understand its negative impacts and figure out how to prevent them from occurring.”

Note: Professor Han is currently looking for dependable students to help in the lab. If you’re interested, contact her at khan@utep.edu.

Related story: Fly Study Could Help UTEP Researchers Understand Human Addiction, PTSD