By Nadia M. Whitehead

UTEP News Service

In the late 1990s, 15 patients with Alzheimer’s disease participated in a clinical trial in Mexico with the drug methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF).

The results were remarkable.

“I remember a family where the woman started dressing herself again – buttoning her buttons and zipping her zippers. She couldn’t do any of that before,” said Mary Boggiano, Ph.D., who went to Mexico to help with the trial and is now a University of Texas at El Paso psychology alumna.

Identified as an ideal drug for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease by Donald Moss, Ph.D., former professor of psychology at UTEP, MSF can improve and prolong memory, delay the disease’s symptoms and help the brain recover from loss so that patients can function more normally – though it does not stop the progression of neurodegeneration.

Studies by UTEP researchers have shown it is three-to-five times more effective than any other Alzheimer’s drugs on the market and has far fewer side effects.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, the first thing that happens is that the brain loses the ability to make acetylcholine,” said Moss, who is a psychobiologist. “Acetylcholine is necessary for memory. If those cells begin to die, you won’t have enough, and you’ll be unable to replace them, so your memory slowly stops working. What MSF does is trick the brain into having more acetylcholine – not making more – but amplifying what’s left of those memory cells.”

And so, patients exhibit improvement.

“They could bathe, comb their hair, eat and make breakfast again – their quality of life was just greatly enhanced,” said Boggiano, who is an associate professor of psychology at The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The team of researchers – made up of Moss; Boggiano; Patricia Berlanga, M.D., a physician specializing in geriatrics in Mexico; and several other students – worked in Chihuahua, Mexico, for nine months to conduct a double-blind study, an experiment where neither the subjects or administrators knew who was receiving a placebo and who was receiving the actual drug.

“Even though we were conducting that study, the families started figuring out who had the drug and who didn’t because they talked to each other and saw the dramatic improvements,” Boggiano said. “And it was funny because the ones on the placebo wanted to get on the drug.”

Despite these capabilities, today – more than a decade later – MSF is still not available for patients.

“I can’t give up; I have a drug that will help people – a drug that works,” said Moss, who retired from UTEP in October so he could devote his full attention to the development of MSF.

With the help of James Summerton, Ph.D., owner of Gene Tools, LLC – a drug company in Oregon – Moss has started the company Brain-Tools, LLC for the sole purpose of developing the drug and getting it to patients.

The two hope to attain grants and crowd-fund some $30 million by the end of the year to help complete the expensive clinical trials.

In addition, the team will apply for Orphan Drug status under the Food and Drug Administration. If approved, it would receive additional funding and aid from the government to help in the endeavor.

“Orphan Drug designation is when a drug is not being sponsored by a drug company because it’s not financially possible to get through FDA approvals, and get money back in the end,” Moss said. “If we can prove that MSF is superior to existing drugs, we can get the government to help us. For now, we need investors and contributors to help us get to the point where we can prove that MSF is better.”

And it is, according to Berlanga, who still recalls the effect it had on her 15 geriatric patients and their families.

“You could see a great difference in their concentration, memory and ability to relate to others,” she said in Spanish. “They had better orientation, and even their families would say it. I can remember one time where one woman said, ‘It’s going to be Christmas soon and I want my mom to be very well, like when they gave her the treatment.’”

According to Berlanga, about 40 percent of her patients suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. She hopes that Moss will succeed in finally developing MSF so that people can learn about its existence and benefits.

“The public needs to be adequately informed about the advantages and disadvantages of existing drug treatments, and the advantages of MSF, because there is a difference between them, and the people noticed,” she said.

If Brain-Tools succeeds, Moss says they will pay everyone back who helped raise funds, and a generic version of MSF will be produced and distributed at an affordable price.

“I saw this work in Mexico. I saw it make patients dramatically better,” he said. “We have to make the company work. We’re not going to make billions. We may not make anything, and it may never make it to patients, but I still have to try.”

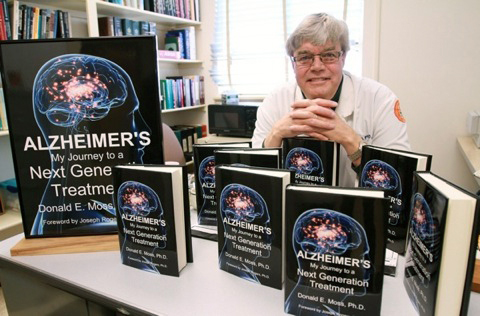

To learn more about MSF, visit www.brain-tools.com or read the latest news at their blog. You can also read about Moss’ journey in his new book Alzheimer’s: My Journey to Next Generation Treatment.