Originally published April 17, 2015

By Nadia M. Whitehead

UTEP News Service

For most women, the annual mammogram is a no-brainer, a routine procedure used to detect breast cancer.

But a growing group of researchers, including some at The University of Texas at El Paso, argue this yearly checkup is unnecessary for certain women.

“For low-risk populations, it would be better to increase the interval between their screenings,” said Wenqing Sun, a doctoral student in electrical engineering. “Mammograms frequently generate false-positives and can be an unnecessary mental burden.”

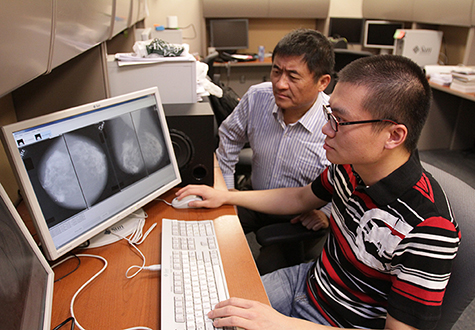

Sun and Professor of Electrical Engineering Wei Qian, Ph.D., point to personalized medicine as a new avenue in breast cancer research. Since some people are more likely to get the disease, the two are working to develop preemptive imaging technology that predicts when and if future cancer will appear rather than detecting existing cancer.

“We’re creating a breast cancer risk analysis system,” said Qian, who runs UTEP’s Medical Imaging Informatics Lab. “It will be able to inform doctors about the patient’s risk of developing cancer within a few years.”

Although not yet complete, the computer-aided detection system has proved pretty successful in early studies. In a paper published last year, the team’s system had an accuracy of 70 percent when it came to predicting which women would develop breast cancer by their next mammogram and which women would not.

“For these patients who don’t have a high chance of developing cancer in the next one or two years, the doctor could suggest coming back for a checkup two or three years later,” Sun explained.

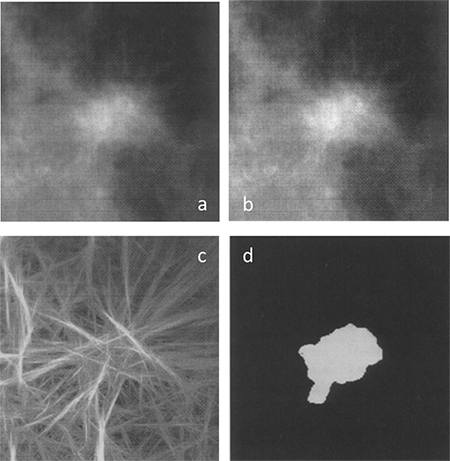

In a real-life scenario, the risk analysis process would begin with a woman receiving a regular mammogram. Sun and Qian envision that the X-ray images would then run through their system, which analyzes multiple features, including texture and breast density.

Breast density is an important factor in predicting the risk of breast cancer. Studies have shown that women with extremely dense breasts are five times more likely to get breast cancer than those with low breast densities.

The technology would calculate overall density and highlight any suspicious areas that are extremely dense, which is a dangerous sign. It also would alert the doctor about any differences between the two breasts.

“Breasts are naturally symmetrical,” Qian said. “But if there’s a loss of balance between the two, that could signify a high possibility that a change is occurring.”

The next phase of the project involves making the system more accurate. The researchers will add in more factors that the computer should consider. These include patient history, the doctor’s analysis, living habits, if the woman has given birth or if she has had hormonal therapy.

“Density cannot be the only feature that the computer looks at,” Sun explained. “We need to look at everything that can affect the patient’s risk and combine them all together for the most accurate risk analysis possible.”

For women who show signs of high risk, the computer would suggest they be screened more aggressively. That might mean getting a mammogram again in the next six months instead of a year.

By separating patients into positive (high-risk) and negative (low-risk) groups, the UTEP engineers believe breast cancer screenings could become more efficient and cost-effective and less worrisome, and save lives.