Originally published July 31, 2015

By Rachel Anna Neff, Ph.D.

UTEP News Service

One day, scientists might be able to use the body’s natural immune response to fight off bacteria and viruses. Thanks to the pioneering research of Charlotte M. Vines, Ph.D., that day might not be too far away.

As part of a $1.51 million, four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Vines will study how the C-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7) regulates the levels of antibodies made during a secondary immune response. The secondary immune response is when a person or animal’s body detects a foreign substance (also known as an antigen) again in the future and creates antibodies to fight that antigen off.

“This research has applications everywhere,” Vines said. “We’re trying to understand how the absence of CCR7 leads to an enhanced immune response.”

The grant officially started July 1. Along with her team of researchers, the assistant professor of biological sciences at The University of Texas at El Paso’s Border Biomedical Research Center has started to examine CCR7’s role in controlling the numbers and types of antibodies produced during the secondary immune response.

CCR7 is a receptor – a protein molecule within the plasma membrane of a cell – that sends the cells on which the receptor is found into the lymph nodes. In particular, the ligands (ions or neutral molecules) for CCR7 are chemokines, which means they are signaling proteins secreted by cells that make cells with CCR7 on their surface travel to lymph nodes. This is one reason why lymph nodes swell when a host’s body recognizes an antigen.

By studying the role of CCR7 within the immune system’s secondary response, Vines plans to expand on research findings that showed current theories regarding the immune system response to antigens do not align with how the immune system actually responds.

Imagine CCR7 as a light switch and the cell as a room. When the light switch is on (when CCR7 is active), the immune system response is controlled and measured. Conventional theories about the immune response are that if the light switch is off (CCR7 is absent or deactivated), the immune system shouldn’t respond because it doesn’t know the cell needs anything done.

Preliminary research has shown this to be incorrect. When CCR7 is not present, the immune system response is delayed, but the creation of antibodies to fight off antigens dramatically increases. It appears as though the job of the CCR7 receptor is to dampen the immune response – and Vines and her team hope to discover why that happens and how being able to turn off or block that receptor might lead to new ways of treating diseases or illnesses using the secondary immune response.

Research has shown that people who do not properly regulate CCR7 have autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Lupus and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Understanding what happens in the absence of CCR7 and the subsequent enhanced immune response has many applications in medicine.

For example, by uncovering what happens when inducing an autoimmune response by turning off a chemokine receptor like CCR7 could lead to future medical treatments in using a patient’s own immune system to fight off a disease or infection that does not have a well-developed vaccine for it such as the Ebola virus or HIV.

There also are possible cancer-fighting applications. By understanding how to turn off these receptors with an antagonist (think of an antagonist as someone going to that room, flipping the switch off and covering the light switch with duct tape), in the future a treatment could be created where an antigen is introduced alongside the antagonist and the body would be able to fight off the tumor on its own by using its natural autoimmune response.

Vines and her team of researchers plan to spend the next four years learning why more immune system activity happens when CCR7 is absent than when it is present. The discoveries and papers generated during this grant period will help the lab be competitive for future national research grant funding.

The grant also provides funding to support two undergraduate students and a postdoctoral scholar. The lab has around a dozen undergraduate volunteers as well.

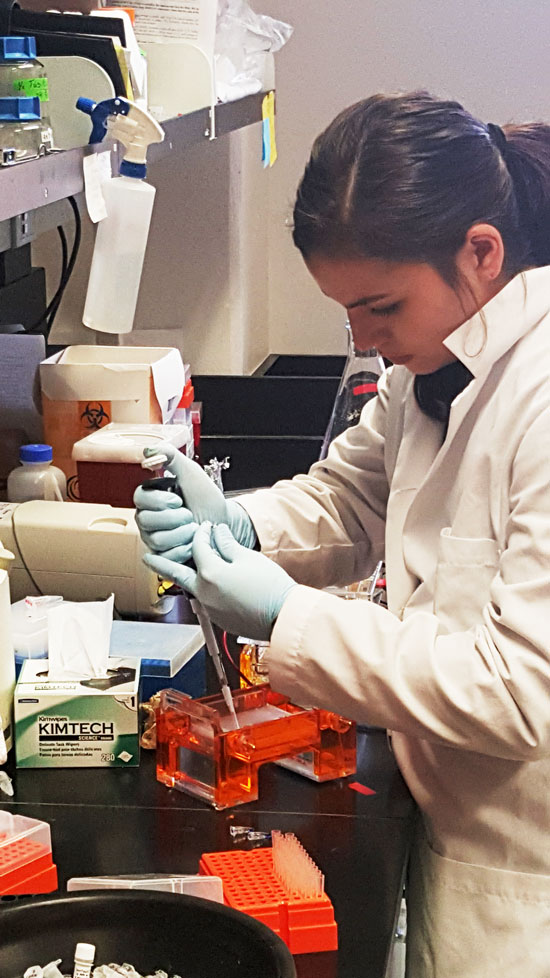

One undergraduate currently working with CCR7 in Vines’ lab is Christina Alvara, a senior microbiology major.

“I got into research at UTEP because, as a sophomore, my TA (teaching assistant) from chemistry contacted me and asked me if I was interested in doing lab work,” said Alvara, who hopes to go to medical school or study for a master’s in biology after she graduates. “I recently had Dr. Vines for a class and I really took to the way that she taught and her personality. I discussed my interest in research with her and thought I was only asking about advice on where to go to do research, but she opened her (lab) doors to me. That’s why I’m here. It’s exciting because this research has implications for vaccines and autoimmune disorders.”

When not guiding undergraduates in the lab, Vines is part of the NIH-funded Work With a Scientist program. The Work With a Scientist program brings high school students to the UTEP campus to perform research in the labs

“I graduated from Andress High School,” Vines said. “I’m an El Pasoan. In the time that I’ve been gone and come back, I’ve seen opportunities be created for students to become competitive nationally. That’s why I’m so happy to be part of Work With a Scientist – six of the kids are from Andress. I’m thrilled because they’re developing cutting-edge research that has implications for future medical breakthroughs.”