By Laura L. Acosta

UTEP News Service

Infectious diseases have no boundaries.

In high mobility areas such as the U.S.-Mexico border, whooping cough, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases such as staphylococcal infection travel back and forth between the two countries, altering the structure of microorganisms and creating a resistance to antibiotics.

In high mobility areas such as the U.S.-Mexico border, whooping cough, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases such as staphylococcal infection travel back and forth between the two countries, altering the structure of microorganisms and creating a resistance to antibiotics.

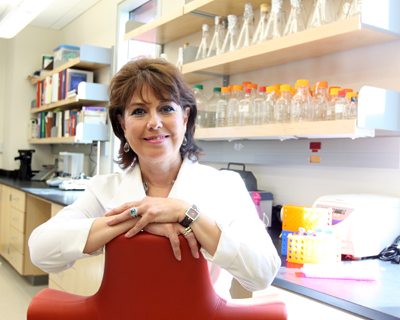

UTEP Clinical Laboratory Sciences Professor Delfina C. Domínguez, Ph.D., is analyzing the genetic composition of microbes in El Paso and Juárez, Mexico to see why the organisms that cause infectious diseases along the border are different from those in the rest of the country.

“The reason appears to be because of the different kinds of populations that are here,” Domínguez said. “There are a lot of problems with anti-microbial resistance. In previous studies we have found that there are certain organisms in El Paso that are a lot more resistant to antibiotics, but then there are others that are more resistant in Juárez.”

Domínguez is collaborating with the University of Hawaii, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and the UTEP-UT Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program to see how the same infectious disease varies in different populations, from symptoms to anti-microbial resistance.

“El Paso and Hawaii are very different but they are also alike in that there is a lot of rapid mobility in the islands,” Domínguez said. “There are different populations in Hawaii and it’s the same thing here. There’s a lot of crossing every day from different people coming from the south.”

By discovering the mechanisms that make organisms resistant to antibiotics, Domínguez hopes the study will lead to better patient care, new medicines and disease prevention education.

Her interest in infectious diseases began when she was a little girl.

Born in El Paso but raised in Juárez, Domínguez remembers being prone to sore throats as a child and asking her doctor why she got sick. The doctor would draw germs to illustrate bacteria such as staphylococcus, and she became fascinated, knowing that something so tiny could be fatal.

Her curiosity sparked her interest in clinical science, so Domínguez enrolled at UTEP, where she saw microbes for the first time through a microscope in one of her labs.

“I was so excited,” she said with a smile at the memory. “I went to my mom and told her that I saw them for the first time – those little devils; they’ll kill you.”

Domínguez received her Bachelor of Science in biology in 1980 and her B.S. in medical technology (now clinical laboratory sciences) in 1982 from UTEP. She also earned a Master of Science in biology in 1987. In 1997, she completed a Ph.D. in molecular biology at New Mexico State University.

Since joining UTEP as a faculty member in 1996, Domínguez has collaborated on several studies related to health issues on the U.S.-Mexico border.

She is working with Mahesh Narayan, Ph.D., associate professor of chemistry, and Jose O. Rivera, Ph.D., director of the UTEP-UT Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program, to develop antibiotics derived from plants. Last summer, Dominguez completed a study on how calcium regulates several processes in bacteria.

In 2008, Domínguez found that the symptoms that we normally associate with whooping cough have changed over the years and can be confused with allergies, which makes it harder to get proper medical care.

“We need more surveillance,” Domínguez said. “(Whooping cough) is coming back and the new targets are the adults. It is like a nagging cough; like a type of allergy. It’s hard to diagnose so people can get this infection and not even know that they have it.”

Her enthusiasm is also inspiring her students to pursue careers in science.

Angie Betancourt, a junior in the College of Health Sciences, met Domínguez in fall 2011 when the aspiring clinical lab scientist volunteered to help in Dominguez’s lab.

Like Domínguez, Betancourt is fascinated by how microorganisms affect the body and how they evolve quickly to survive. She was also impressed by her future job prospects.

“When I went to talk to [Domínguez], she told me about the program and she presented it so nicely,” said Betancourt, whose dream is to work for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “You can find a job right away as a clinical lab scientist because there’s a shortage, so that’s what attracted me.”

According to Lorraine Torres, clinical assistant professor and clinical laboratory sciences program director, there are approximately 238 clinical lab sciences programs in the United States, which graduate about 5,000 students per year. However, there are more than 10,000 jobs available for graduates.