By Daniel Perez, UTEP Communications

One of the most festive celebrations to hit El Paso since Don Juan de Oñate crossed the Rio Grande erupted the evening of March 19, 1966, and the party continues in the hearts and minds of diehard Miners. The NCAA basketball championship has been a seminal point of pride for The University of Texas at El Paso ever since.

Fifty years later, much is made of the decision by UTEP’s Hall of Fame Coach Don Haskins to start five African-American players against the all-white University of Kentucky Wildcats. That decision had a ripple effect on college athletics and a nation still adjusting to desegregation and passage of the Civil Rights Act. However, at the time, the only color the Miners cared about was orange and the only score they wanted to settle was the final one at the University of Maryland’s Cole Field House in College Park, Maryland.

Fans remember the game and the ensuing celebrations as if they were yesterday. It galvanized a community and brought notoriety to the small independent college in far West Texas. After the final whistle was blown at about 10 p.m. El Paso time, thousands of people began to congregate around what is now Centennial Plaza to celebrate.

Most of the revelers were content to hug and holler, but a few decided to up the antics. Some nameless pranksters opened a fire hydrant in the party zone while others collected kindling and started a bonfire at the southeast corner of College (now University) Avenue and Hawthorne Street. Those who were there speak about the moment as if those flames never died out.

During the past 50 years, UTEP has celebrated that underdog 72-65 victory as one of its greatest achievements. The story is part of a family history handed down from one generation to another. It is a passing of the torch. It is UTEP’s eternal flame.

In the beginning …

Haskins, who died in 2008, argued long and hard that his decision to start five African-Americans in the championship game, a move that had never been done before, had more to do with wanting to win a game than to make a social statement. So be it, but the team may not have had those African-American players if UTEP, then Texas Western College, had not been the state’s first senior college to desegregate at the undergraduate level in 1955.

El Paso, a community of more than 300,000 at the time, was made up mostly of Caucasians, Hispanics, Mexicans and everyone Fort Bliss brought in from other states and other countries. The college enrollment was more than 7,400 and the campus had about 28 buildings, not counting Greek houses and playing fields.

Willie Worsley sophomore guard in 1966: It was eye opening. I was used to tall buildings (in New York). El Paso had tall mountains. The campus was small, but growing, and that’s what I liked. I didn’t want to get lost in the sauce.

Jerry Armstrong senior forward: I made my recruiting trip out there and fell in love with the campus and El Paso and decided to sign there. I came from a small farm (in Missouri) and had hardly been out of the state. I remember the weather was nice, not like the cold weather in Missouri. It was a great transition for me to go to a large city that was predominantly Hispanic. I got to see a lot of different cultures. The people seemed nice and were supportive of the athletic program.

Fred Schwake student assistant trainer: It was a typical small commuter college. You could shoot a howitzer down the middle of College Avenue after 3 p.m. on a Friday and not hit anybody. There weren’t that many people. I guess that brought us closer together.

David Lattin sophomore center: I liked the atmosphere. It was very liberal. Everyone was friendly. (Jim) “Bad News” Barnes, who was there at the time (1964), challenged me to come back and break all his records.

Joe Gomez freshman history major: I didn’t expect to see so many students from out of town. I met people from New York and the Carolinas. It was a great atmosphere. There were clubs and fraternities and sororities. The dorms were full, and students didn’t miss any games. The professors seemed to know everyone by their first name.

Pam (Seitz) Pippen sophomore cheerleader: El Paso was small and easy to get around. Texas Western was like a high school on the hill. You knew everybody. There was not a lot of transition. There were a lot of activities, but they were the same as in high school. It was a close-knit community.

Dick Myers junior forward: I flew in from Kansas and fell in love with El Paso from day one. The desert was different and I loved the mountains. The first thing I noticed about the campus was the architecture. It was a good-sized campus for me and everyone was friendly.

Team formation

Haskins, with the help of his assistant coach Henry “Moe” Iba, recruited and molded a team that could be explosive offensively, but was drilled and skilled at defense. The team was supported by head trainer Ross Moore.

The head coach, who would end his 38-year career in 1999 with a 719-353 record, was a tough, focused disciplinarian who got the most out of his players. They respected him and, in a few cases, feared him. He was known for his dominating personality and great basketball mind on the court and his sense of humor and laid-back style off of it.

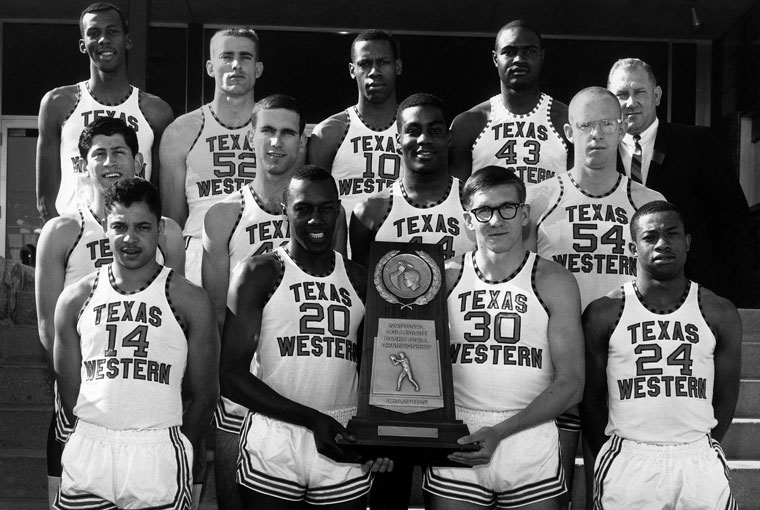

The 1965-66 Miners were a combination of players from around the city and around the country. They were hard-nosed and hard working in general, but each brought their specific skills to the court. They were leapers and leaders, ball handlers and shooters, defenders and rebounders, inspirational and encouraging. They were versatile and confident to the point of cockiness. From starters to bench players, all were important cogs in Haskins’ machine.

Moe Iba assistant coach: Bobby Joe (Hill) was a different type of cat. Don tried to change him, but he realized it was best to just let him go. He was one of the quickest guards I ever saw. He had amazing ability. I think (David) Lattin was the key to winning the championship. He was so strong. He could rebound and shoot from inside and outside.

Jerry Armstrong: We each had a role. (Harry Flournoy) was that spoke on the wheel that made us that much better.

Dick Myers: Bobby Joe (Hill) was the heart and soul of the team. He had a way about him. He wasn’t a great shooter, but when you needed one, it went down. It was great fun watching him play. It was fun watching everyone, but him in particular.

Moe Iba: The only goal was to make the team realize that they had to get better every day, and they bought into the system. They thought they would be successful. They had confidence. If anything, Don had to work on that. They needed to keep their heads on right because they all knew they could play.

Home court advantage

The players encouraged their classmates to attend the games at Memorial Gym, a relatively small venue designed to seat 4,000 on the northwest side of campus. It opened in 1961, and as the basketball team’s level of success improved, so did its fan base. By the 1965-66 season, the college had added 16 sets of retractable wooden bleachers that expanded capacity to around 5,200 who turned the gym into an intimidating, ear splitting box of thunder.

Willie Cager sophomore forward: [Memorial Gym] was a ferocious place to play. There was a lot of yelling and screaming. It was something. It was always packed. There were people under the bleachers trying to watch the games. It was like no other venue.

Linda Sue (Perkins) Spitzer sophomore cheerleader: That place was packed with an energy you could feel. I recall one of the players remarking that the team could feel the floor and the walls vibrate while they waited in the locker room.

David Lattin: It was compact and very cozy. Our opponents hated it. They knew there was an excellent chance they wouldn’t win.

Louis “Flip” Baudoin junior forward: I don’t remember ever playing a game in Memorial that wasn’t a sellout. I didn’t envy the visiting teams. It must have been miserable. I attribute my current hearing aids to that time in my life.

Dick Myers: The stands were so close to the floor that it was like having an additional player. In close games with all the yelling and screaming, it certainly could be intimidating. It was an advantage for us.

Pam Pippen: It was a hard ticket to get. The gym was always crowded. It was often standing-room only. It was easy to get fans involved. Everyone knew the chants: ‘Two bits, four bits, six bits, a dollar, All for the Miners, stand up and holler.’

The championship game

Although ranked as high as third in the polls, Texas Western College was still an unknown commodity around much of the country. On the other hand, Kentucky and its legendary coach Adolph Rupp already had won four championships and were favored to win in 1966. The crowd at Cole Field House was pro-Kentucky and several Confederate battle flags were being waved in the stands. Haskins said the reason he started sophomore guard Willie Worsley was to counter Kentucky’s fast break. It turned out to be a brilliant strategic move. The game’s big momentum switch happened after Bobby Joe Hill’s back-to-back steals in the first half that led to layups and a Miners lead that was never relinquished.

Mary Haskins wife of Don Haskins: We had a good crowd from El Paso, but the majority of the people were for Kentucky. It was not hostile, but it was not the warm feeling you’d like to have.

Pam Pippen: I noticed the rebel flags in the arena, but my only reaction was a shrug. I heard people saying that Kentucky was going to win and that the television cameras were already in the Kentucky dressing room. I went to the restroom and someone asked me if we would hug our players if we won. They had more of a sense of the racial discrimination. I stayed focused and tuned out the crowd.

Jerry Armstrong: I saw some (Confederate) flags flying, but it didn’t affect us. It wasn’t a black or white issue to us. It might have been that way for Kentucky fans, but that was their problem. Starting five blacks is something we had done all year. Kentucky was just another team we had to beat. They had been there before. They were supposed to win. No one had heard of us. We didn’t get the (press coverage) from the media out east, but that worked in our favor. That motivated us. The pressure was all on them, but we wanted it worse than they did.

Moe Iba: We had no doubts we could beat Kentucky. We thought we had played better teams in the tournament. Cincinnati and Kansas were better. You could see in the faces of the Kentucky players that they had never played against guards as quick as ours or a player as strong as Lattin.

Joe Gomez: There were about 20 of us watching the game on a 19-inch black-and-white TV with aluminum foil antennas at the Tau Kappa Epsilon frat house. That first dunk (by Lattin) set the tone. The message was that we were going to be aggressive.

David Lattin: Coaches from prior games had complained that we were a rough bunch, so the referees were especially looking out for me to make sure I did not take advantage of anybody. My main concern was how I was going to stay in the game.

Willie Worsley: We felt disrespected. We were ranked No. 3 in the country and everyone thought the champion would be Duke or Kentucky. When coach gave us the starting lineup, he said the four and then he said, ‘Willie,’ so I turned to Cager and said ‘Go get ‘em.’ Then coach said, ‘No, it’s you little one.’ I was happy and ready. I’m from New York; I was ready to play ball.

Willie Cager: I came in and guarded (Pat) Riley and got the team to settle down. I played defense. Defense wins ballgames. All we wanted to do was win the game. From the beginning of the game, we knew we were going to win. It was automatic.

David Lattin: Coach Haskins was a defensive coach so we didn’t have to change anything. He just told us to ‘Go out there and continue doing what you’ve been doing and you should be successful.’ We always felt that we were going to win. You never really know, but we had supreme confidence that we would win the game. Our game was mostly about defense, so we forced other teams to play at our tempo. We took Kentucky out of their game plan.

Louis Baudoin: As the two teams squared off, it quickly became apparent just how different we were. The Miners played full-court defense and were patient on offense. Kentucky was in a hurry and we were not. Watching it play out from the bench was very interesting. Our team felt as though the game was being played at our pace. There was a level of frustration from Kentucky and we fed off it. When it was finished, our players were physically exhausted, but if we’d have had the chance, they could have reset the clock and we’d have been happy to go another 40 minutes.

Barnard Polk Miners fan Class of 1977: I was a big fan of the team and attended every home game that season. Unfortunately, the night of the championship game I was committed to attend Austin in Action at the El Paso County Coliseum. It was one of the high school’s biggest events of the year. I was there physically, but my heart and mind were in Maryland with the Miners. Everyone felt the same way. I couldn’t stop thinking about the team. One of the other members of the court, Bob Geyer, brought his transistor radio and its earpiece, so he would whisper updates to us as the pageant introductions were being made. We’d pass the information along the stage. It was pretty exciting. I found out the final score from my dad, who was one of the chaperones. He was watching the game on a small TV under the coliseum stands. Frankly, I don’t know how much my parents saw of the pageant. Oh, what a night. I wish I had seen it or heard it, but they won. That’s what counted. Soon everyone at the dance knew the score. It took the atmosphere way up.

Sue (Moore) Manning sophomore cheerleader: After we won the championship, a newsman with a microphone stepped between me and the jubilant players and asked me what we were going to do now, and I answered that we were going to have a victory party at the motel. He said, “No, are you going to hug and kiss those black boys?” I was stunned. That’s when it hit me that they were also upset by our team’s racial makeup.

The party

Riley Bench Hall The Prospector sports editor: Judy (his wife) and I were watching on a black-and-white Zenith in our two-bedroom student apartment across from Memorial Gym. It was a close ballgame. When the game was over the families started to flood out screaming, hooting and hollering, and heading to campus, where people began to congregate and celebrate. One kid climbed the flagpole. It wasn’t a drunken crowd, but it was exuberant. Someone started the bonfire with old lumber and the fire department could not get to it because of all the cars. The worst part about the fire was that it melted some of the asphalt. Some students got a wrench and opened a fire hydrant and the water was shooting out with tremendous force. A Cadillac drove by and someone opened the car’s door and it was filled with water. Everyone was having a good time. It was the experience of a lifetime.

Joe Gomez: The first thing we did was come to campus. People were all over the place. It was a wild, wild scene. Someone had opened a fire hydrant and others had started a bonfire using scraps from a construction project. The fire department parked around Oregon and University. I give credit to the authorities and the students. There were no arrests and no cars were burned or overturned. From there we went to San Jacinto Plaza Downtown where there was more healthy celebrating. We were honking our horn. I saw people embracing. It was an incredible celebration. The next morning, several thousand people went to the airport to welcome the team back. We stood 10-12 deep. I remember seeing the trophy. I went home after that. It had been a long overnight celebration, but the excitement lasted through the end of the semester. People couldn’t get enough.

Pam Pippen: After the game we went to a formal event and were bored to tears. We went to the hotel and called our friends in El Paso and heard about the bonfires. We felt like we were missing out on the celebration.

Willie Cager: I celebrated with family and friends after the game. It was nonstop. There were probably around 10,000 people waiting for us at the airport. I thought to myself, ‘God almighty this is a big crowd.’ I told the crowd at the airport, ‘From all of us to all of you, No. 1 is the best we could do.’

David Lattin: Every person who could breathe was out on the street, at the campus or at the airport. It was a great time.

Louis Baudoin: As a team we were tickled not to have practice the next day.

And then what …

People returned to work and their studies by Monday morning. Hall and a few others had to quickly turn around the final sports pages of the ’66 yearbook, The Flowsheet, which the publisher delayed to allow the college to record the game outcomes and celebrations. The team members were big dogs on campus, but the spring semester ended and people and the players moved on to the next thing. Iba went on to be a head coach at several Division One programs. The players went on to successful careers in education, athletics, business and law enforcement. Many of the educators also coached basketball. Most are retired, but remain active in their communities around the country. Hill retired as an executive with El Paso Natural Gas and died of a heart attack in 2002. Haskins was elected into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1997. The team was inducted 10 years later. In February 2006, the team was recognized at a White House dinner hosted by President and Mrs. George W. Bush. It was accompanied by a screening of the Disney film “Glory Road,” based on the Miners’ 1965-66 season. The team remains the only institution from the state to win the NCAA men’s basketball championship.

Jerry Armstrong: I had a lot of people ask me why I didn’t play in that game. I was happy that we won, but it bothered me a little. I never asked Coach Haskins about it, but about 10 years ago he told me, ‘Jerry, I should have played you.’ I respected that because it wasn’t his style to apologize. It all worked out. We made a little history.

Willie Worsley: It is an honor that people still call me after 50 years and want to talk about that experience.

Dick Myers: When we won the championship, I thought those were my 15 minutes of fame. Then the movie came and the Hollywood premiere, dinner at the White House, and the Hall of Fame. I think I’m at about two hours (of fame) at this point and we love it. I love seeing the guys. It’s kind of like family. We don’t see one another for a while, but then we get together and tell the same stories and we’re ready to go. Other than my wife and family, that team was the best thing that ever happened to me.